It is the last of the month, which means payday in Johannesburg, and the working class is out to enjoy the happiness of a sunny winter Saturday. Behind the tall walls topped with barbed wire that define this city, the sun does not rise until later, safekeeping the few from the sun’s universality to uphold a white complexity that has taken centuries of division to maintain. Outside these walls, the sun is shining high, and the locals have a spring in their step as they walk along the highways that connect this massive urban hub, raising their hands to form specific meanings depending on their intended destinations.

As we drive further into the city’s southwest, Big Mike – born and raised in Soweto – tells us about the significance of this place not only for the big Josie, but for all of South Africa. Created by the apartheid government in the 1930s to house Black South Africans, Soweto – short for South Western Townships – was a centre for the Black resistance and home to the immortal Nelson Mandela. Here, in Soweto, the less opulent walls and gates are more of a mere formality, home to a proud up-and-coming Black middle class. In the rest of Joburg, the gated white communities not only represent status but also cement an abysmal social inequality, defended by the thousands of warning signs advertising armed security services.

Our first stop in Soweto was a massive flea market where garbage-eating goats roamed free close to an open-air butcher, behind which a pile of horns and bones festered with green flies painted the picture. Considering we arrived in a big white van and were the only tourists anywhere to be seen, we were a bit hesitant at first, mainly because of the several warning speeches we had been given beforehand. South Africa is, in the end, a very dangerous country, with some 64 murders a day, but I believe that the problem lies not so much in the picture, but how it is painted, perpetuating racial division. We were greeted by an elderly man, a local public figure dressed in a modest yet proud suit, who promised to give us a tour of his neighbourhood. He started by welcoming us into his house, the same house where he had been born many decades ago: a small, yet proud concrete enclosure that the locals call ‘matchbox houses’. He topped the South African hospitality we had been forewarned about by offering us a handful of clear water from the tap that supplied his and his immediate neighbours’ homes.

As we crossed the road and dwelled back out onto the market and further into the Soweto experience, people nodded their heads in respect for the fact that we made it out there. Unemployment rates in South Africa round up the 40%, but in these markets, it becomes evident that it is not for lack of trying. People will sell any and everything, from a wide range of sunglasses, leather belts, and interwoven bead necklaces, to bags of peanuts, to just try to get by. We were introduced to one of the local ‘witches’ and shown how traditional African medicine is well and truly alive. All you have to do is specify your ailment, and the local doctor selects from the dozens of species of bark, spices and other unknown condiments to put a drink together in a plastic bottle. A couple of good shakes and you are on your way. Our guide also showed us to the local taxi station, the main form of transportation for the South African working class. These Hiace minibuses typically carry 15 to 16 people, and considering that public transport is practically non-existent, they control the industry and their territory. We were told that because these do not set off until they are completely full, you will see people dancing and singing inside them to try to lure people in so that they can get on their way quicker. Taxi drivers are notorious for their known violence and turf wars, but apart from a few loud whistles and lots of shouting we couldn’t understand around us, we had no issues.

By the time we had been walking around for a good hour or so, we felt well at ease. One local guy carrying a shopping bag got out of his way to fist bump us and welcome us to South Africa, shouting that we were loved out there. The warning monologues designed to keep tourists from mingling with the Black community slowly started to vanish into thin air, along with the smoke of the charcoal brai, the South African version of a BBQ and a vital part of their culture. As we shared a few boerewors and peri-peri chicken pieces on the side of the road, people greeted us and shook our hands in welcome. By the time we got back into the van, our perspective had shifted completely.

Our next stop was a massive settlement or ‘shanti town’ in East Orlando.

We were welcomed by another local based there, who took us for a tour of their everyday reality. These small shacks are put together by pieces of scrap metal, many of them insulated by discarded tissue or old carpet. Barbed wire laces the sides of some of them, not so much for security, but more as an effort to improve structural integrity. Live wires hang overhead and beside you, so you are forewarned to watch your step.

Small children roam freely with curious eyes, hoping to score a piece of candy, only to vanish around a corner again. We met one of the local women who had put together a small shack with dirt floors as a kindergarten for the many children living there. As we stopped amid the narrow walkways connecting the settlement, our guide told us how racism, corruption and nepotism perpetuated the growth of these settlements. He also told us how laws in the constitution protect illegal settlements such as that one from displacement. The eloquence with which he painted this picture shone a light on the proud education system of this country and its vital role in Black emancipation.

From there, we were taken to another must in the Orlando experience called Meat Meet. This amazing business model consists of a car wash with an alfresco next to it. You pull up in your vehicle, walk up to the counter, choose what meat you would like – it is still raw for your perusal, much like a butcher – and from there, your toughest decision will be the brand of beer to wash down your meat cooked to perfection.

If the three-metre long brai with a perfect bed of white coals does not get your blood flowing, do not despair, for it is served with pap, another staple of South African cuisine consisting of maize meal and water – much like a sturdier white polenta – paired with a selection of slaws and garnishes. To my great satisfaction, we ate with our hands for the first time there, and the way you grab your pap to avoid meddling with everyone’s food is an art in itself.

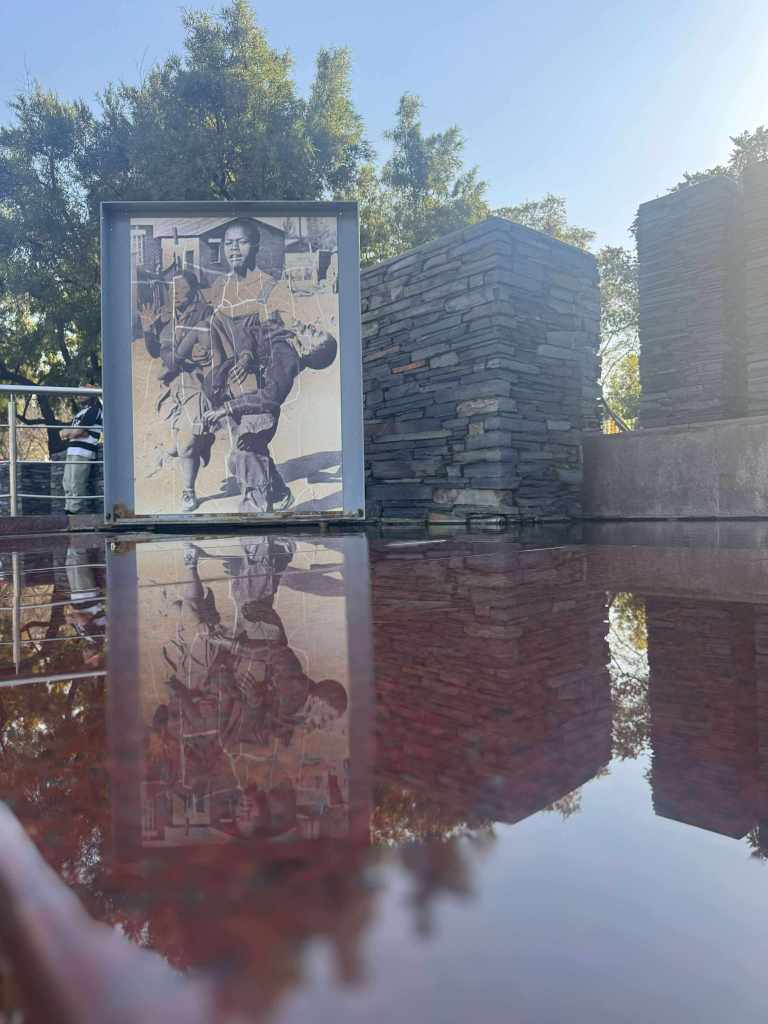

Our next stop was in Orlando West at the Hector Pieterson Memorial, where we learned about the 1976 Soweto uprising. Here, we were educated about a pivotal moment against apartheid in South Africa where thousands of students got together in a peaceful protest against the use of Afrikaans in schools. This memorial marks the exact spot where the 12-year-old was shot and killed by policemen, which led to the deaths of hundreds of students and Black South Africans all around the country. Again, the sheer pride and eloquence of the guide for this memorial were evident, and the landing of a dove above us on one of the African olive trees spread around the square was a highlight. Events such as the Soweto uprising raise the question of how social inequality is still evident in the country some 50 years on, and how many people died over the years to fight against it.

From there, a short walk will take you to Nelson Mandela’s house, a modest home with gunshot bricks and a Melaleuca tree in its backyard where his children’s umbilical cords are buried. The buzz around this place is evident, with Zulu acrobatics of dancing and traditional singing marking the transcendent cultural importance of Madiba. The several pictures of his family around the place – many of which are now deceased – show how his spirit lives forevermore in the country’s core identity.

As this adventure of a day was coming to an end, we took a short walk around the corner from Madiba’s house and arrived at The Shack, a secluded local bar serving nothing other than 750ml bottles of Soweto Gold, their trademark beer.

We were treated to the presence of several locally infamous characters and were definitely the local attraction for the afternoon, but never once felt insecure. This was by far our most adventurous outing in South Africa, but the locals seemed to rejoice at our presence, and the only issue was simply overexcitement. We were told that in South Africa, seeing a Black and a White man together will bring you luck, and the whole of The Shack seemed to rejoice in this as the one single speaker blasted dance music in celebration.

As the sun started creeping behind the concrete walls and our Soweto adventure neared its end, the love and warmth we had received throughout the day had us all smiling, our hearts full.

Most tourists who land in Johannesburg set off to Kruger National Park straight away – which is a gem in itself and well worth the drive. But in the end, Joburg is a hugely diverse place with a lot of peace, love and unity to offer – as expressed by the local handshake. Sure, the chances of turning the wrong corner are high, but with elevated unemployment rates and unfathomable inequality, it is easy to blame the end product and not the system that perpetuates it. It does beget the question of whether the divides in this country are echoes of a past that the select few choose to hang on to. South African people are proud of their culture, and Soweto is the perfect example of this. And if you are willing to push past the prejudice and the idea that this city is too dangerous to visit, you might just experience one of the most rewarding cultural journeys in your life.